At first glance, library versioning seems like a simple task: just follow the rules of semver. However, what if you decide to create a monorepo with multiple libraries? In that case, it’s not as straightforward as it appears. Developers often start with a basic approach and, when faced with challenges, gradually move towards the most optimal solution. In this article, I will discuss the main approaches to versioning and the problems that arise, so you can quickly navigate these pitfalls and immediately choose the best option. This article will be useful for those who develop libraries, create monorepos, or are curious about the reasons behind the versioning system of popular libraries.

Option 1: Versioning a Single Library

This is the simplest method when you only have 1 library containing isolated code.

Formula: Library A has its unique version. For instance, lib-a is versioned 1.4.0.

This approach works great when you have a single, straightforward library. If possible, this option should be preferred.

Reasons for Creating a Monorepo

Although having one library with a single version is a good choice, it can lead to the following issues:

- The library might become too large.

- Most of the functionality may not be used by users, but will increase the size and number of dependencies.

- One package might contain code for different purposes - backend, frontend, testing, configurations of third-party tools, which adds complexity both in terms of configuration and usage, as well as tree shaking.

- Creating libraries built on modular/separate plugin/package architecture. This is to split the code and allow for parts to be replaceable.

To address these issues, we might consider a monorepo, which I will discuss further.

Option 2: Versioning multiple libraries in a monorepo with individual versions

When creating a monorepo, it’s possible to continue using the approach of individual versions for each library. In the initial stages, everything will be fine, and libraries will share the same major version without any discrepancies. However, as time goes by, say a year later, the monorepo might find itself in a situation where the libraries have different major versions.

Formula: Libraries have distinct, unrelated versions. For instance, lib-a is at version 2.1.0, while lib-b is at version 1.3.0. If you update lib-a to version 2.2.0, only lib-a needs updating.

Challenges with this approach:

- Difficulty in choosing a version for library users - It becomes hard for users to discern which versions of the libraries they should select. This may necessitate creating version compatibility tables, which can be cumbersome and unintuitive.

- Testability issues - With which version combinations of the libraries will the entire library suite remain stable? Typically, in such cases, the correct answer is: with the latest versions of all dependencies. As these recent versions are typically rigorously tested. However, if you need to figure out which dependencies to use with a version like

3.8.0from four months ago, you’ll face challenges, and determining the right combo isn’t straightforward. - Emergence of different library versions - As the number of libraries grows, you might encounter situations where users combine incompatible versions. This can happen if a user updates Library A, neglecting the others. Consequently, the project could end up with a lot of duplicate code.

In summary, I wouldn’t recommend this approach and would advise exploring other options. However, there are specific instances where this method can be applied — when the libraries are not interconnected and don’t reuse each other’s functionalities.

Option 3: Versioning Multiple Libraries in a Monorepo Using 1 Common Version

After facing certain issues, you might reconsider your approach and shift towards a strategy where there’s one common version for all the libraries in a monorepo.

Formula = N libraries have the same version. For instance, lib-a and lib-b both have version 1.3.0. If lib-a is updated to version 1.4.0, you also need to update lib-b to version 1.4.0.

Problems this approach solves:

- Difficulty for users to choose a version - It becomes simpler for users to select a version, as all the libraries carry the same version. This holds true for both new and old versions.

- Testability issues - Libraries within the same version will be tested.

Challenges with this approach:

- Every library update triggers updates for all other libraries - - If you update Library A, you’ll need to release new versions for all other libraries (e.g., 10). However, this isn’t typically a major concern, since npm packages are lightweight and don’t put much strain on the registry, making it a manageable situation.

- Tooling should be capable of updating all dependencies at once - There arises an added demand for the tooling to be adept at instantly updating all dependencies and accurately handling versions. Not every tool can accomplish this.

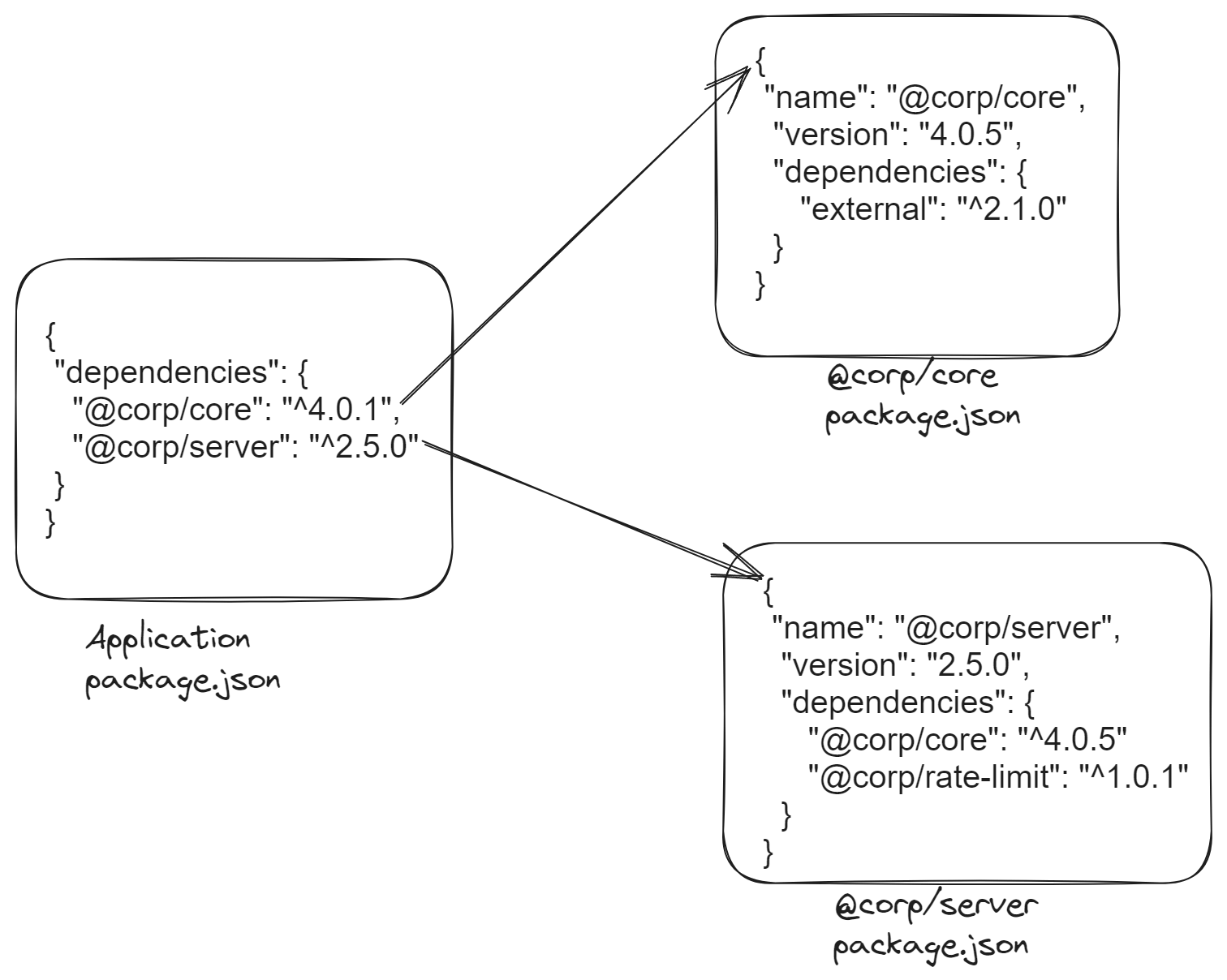

- Users might encounter issues with partial updates - A developer might update only 1 dependency, leading to potential problems. If internal libraries use the

^for versions, like `^4.0.1“, duplication might occur, where some versions are updated while others remain unchanged, potentially leading to unexpected errors.

Option 4: Pinning Internal Dependencies and Additional Tools for Version Updates

After encountering some issues, you might start refining your schema, arriving at an approach where all libraries in the monorepo use a single shared version, and internal dependencies are pinned to a specific version. Additionally, you’ve developed a tool to assist users of your library in updating versions.

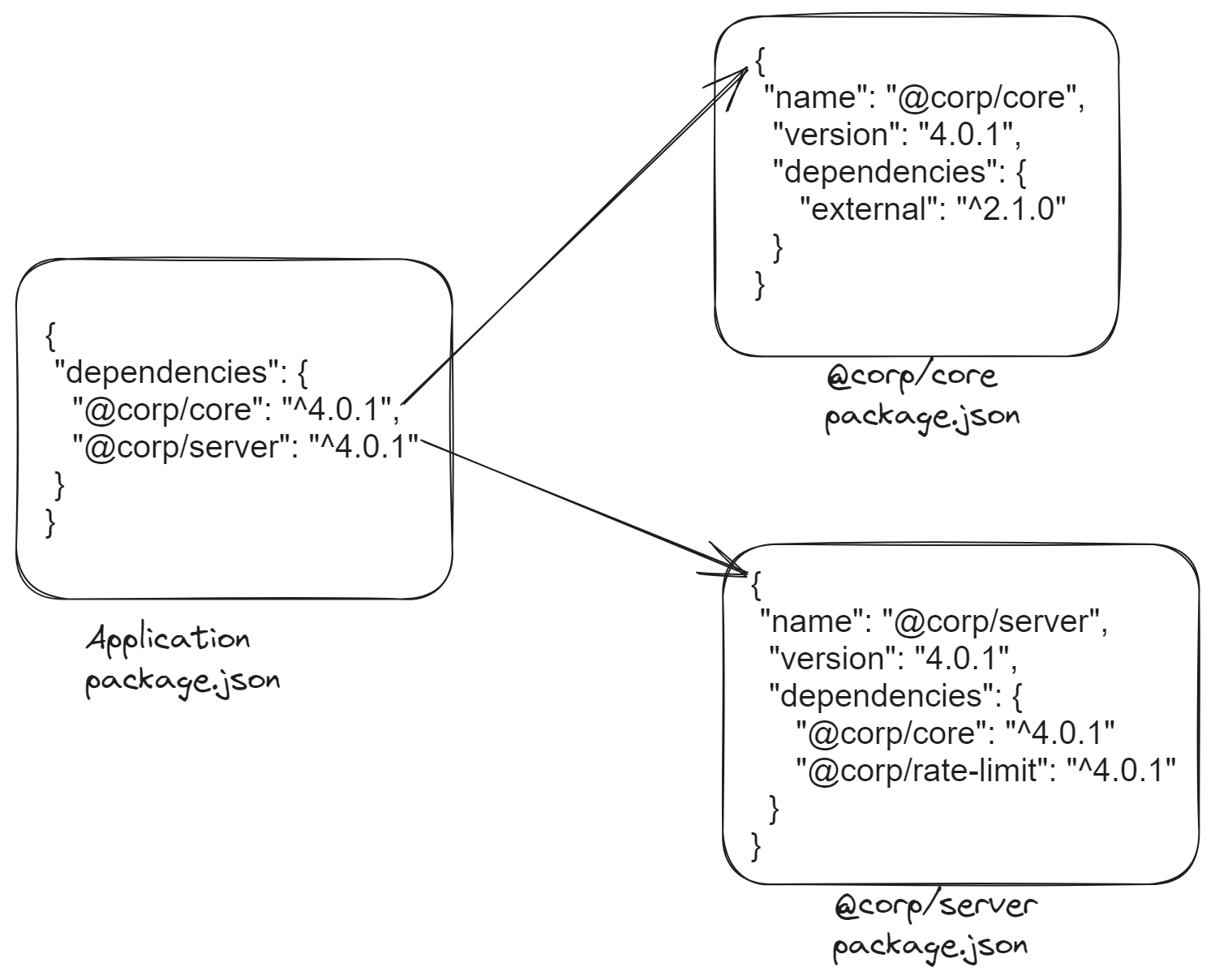

Formula: Every library has the same version. For instance, lib-a and lib-b both have version 1.3.0. When updating lib-a to version 1.4.0, lib-b should also be updated to version 1.4.0. Internal dependencies are pinned to a specific version, e.g., lib-a depends on [email protected].

Problems this approach solves:

- No accidental dependency updates - when updating dependencies or resetting the lock file, dependencies won’t be accidentally updated as they are pinned.

- Users may still use the wrong version - a user might not update dependencies for a year, and during that time, you might release major versions of the library. Afterward, if the user runs the command

npm i @corp/feature-toggle, multiple duplicate dependencies will appear in the project since@corp/feature-togglewill be using a new set of dependencies.

Utilities for Updating/Adding Libraries

To address the issue of library version verification, we can develop an additional tool that checks the library versions installed in the project and simplifies the update/addition process. Some features include:

- Separate commands like

myLib update 2.0.0ormyLib add @corp/feature-toggles, which will update all libraries to the desired version and ensure the package.json and lock file don’t contain duplicates or discrepancies in versions. Example of code - Separate checks after installing dependencies to ensure that all library versions are compatible and free from duplicates. We can add a postinstall command in npm that will automatically run when installing or updating dependencies.

With the introduction of such tools, it will be easier for users to update library versions if they utilize the suggested utilities.

Additional Features

Dealing with External Dependencies

External dependencies are those we don’t develop ourselves but actively use in our libraries, such as React, Fastify, Vue, and many others. It’s challenging to lay down a specific rule, but some advice can be provided:

- Don’t pin versions of major libraries — avoid specifying exact versions for “big” libraries, like

[email protected]. Being strictly dependent on a specific version causes a lot of difficulties for users of your library since they might want to use a newer version or patch vulnerabilities. Pinning versions requires more time spent on updating them. - In some cases, avoid pinning the major version — for instance, don’t pin the React version like

react@^17. This library rarely updates by itself, has a stable API, and the latest releases (17, 18) haven’t had many breaking changes on average. Pinning a major version demands additional time for updating all dependencies. In this case,react@>17would be suitable, but understanding the specifics of the library is crucial. - Pin versions when they won’t work with others — sometimes, there might be bugs in the dependencies. For example, a new version of

[email protected]is released, and you know your code won’t function with this new version. In such cases, it’s a good idea to temporarily pin the version to[email protected]

Should All Libraries Have a Common Version in a Monorepository?

I’d recommend segregating some libraries from the main monorepository version to their individual versions if:

- They are general-purpose libraries that could be frequently reused in other libraries not governed by the monorepository. For instance, you could develop a logger for your company that will be reused in other major libraries. In such cases, each major version creates many duplicates, so it’s better to have a separate version.

- There’s low interdependency with the rest of the code.

How can this be implemented? Let’s say you have @corp/code and @corp/server, both versioned at 5.5.0, but there’s also a logger, versioned independently at 2.1.0.

Conclusion

For projects, I advise using Option 1 for simple libraries, and for monorepositories, opt for Option 3 and Option 4 (over time). This approach helps to address many issues and is generally accepted within the frontend community. Examples can be seen in various libraries: