Cache is a crucial component of many systems. It helps reduce resource consumption and improves the timing of our systems. Often, I’ve observed the Node.js community focusing on the speed of cache algorithms. However, a cache algorithm primarily has two parameters: hit rate and speed. In this article, I will introduce a new cache algorithm, S3-FIFO, which promises to enhance the cache rate compared to other popular cache algorithms. I will also identify potential deoptimizations in my code. This article will benefit those eager to learn more about caching and algorithms.

What is Cache?

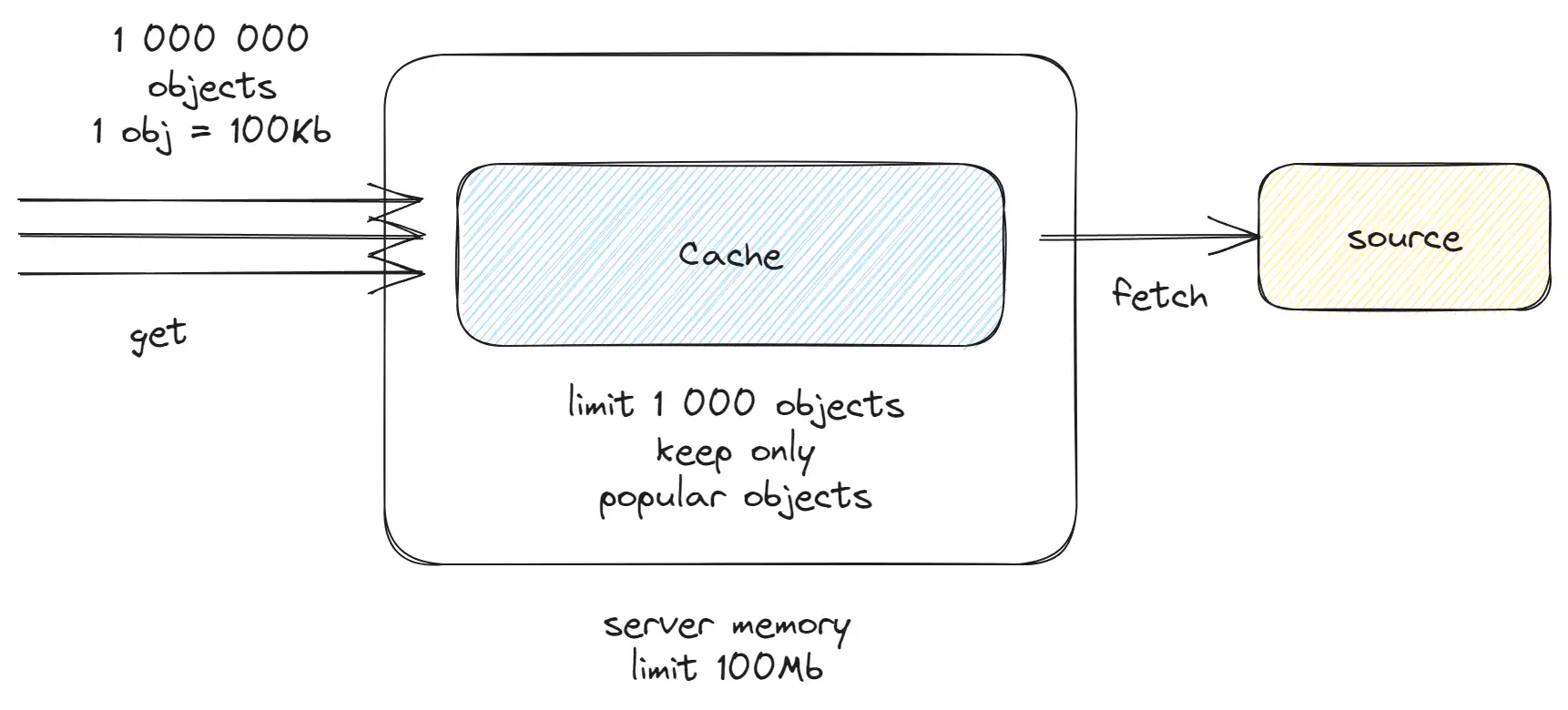

Caching prevents unnecessary CPU/response time for tasks that have been previously completed. Take CDNs (Content Delivery Networks) as an example. Every CDN node has an internal cache that stores popular objects and delivers them to users. This boosts performance since the CDN can retrieve the response from memory without waiting for a request to reach the server. However, servers have a finite amount of memory, say 1GB, and cannot store all objects in memory, especially when processing large amounts of data. To solve this problem, engineers use caching algorithms, which allow to fit within the memory limit and store only demanded objects

When Should We Use Cache?

Caching introduces overhead to your applications. It’s not suitable for every function. We should opt for caching when the response/CPU time outweighs the cache costs. Also, consider the volume and type of data:

- For static, unchanging, and limited data, a simple Hash map without cache algorithms suffices.

- For dynamic data, cache algorithms become essential.

Examples of when caching can be beneficial:

- Caching assets

- Caching database queries

- Caching requests

- Caching resource-intensive functions

Every 1% Hit Rate Matters

A 1% hit rate can significantly save CPU time. Imagine having 1,000,000 requests per second, with each request costing 10ms of CPU time. A 1% hit rate can save 100,000 ms or 100 seconds of CPU time. For instance, a 50% hit rate would save 5,000 seconds of CPU time (equivalent to 5 CPU cores). Thus, if you handle numerous requests, it’s crucial to strategize on improving the hit rate to save resources.

Main Challenges with Cache

I won’t go into the topic of invalidation, but caching contains other interesting challenges.

Popularity Attack

A challenge with the LRU (Least Recently Used) cache is its design, where there’s a single queue or double-linked list containing all elements. If your workload involves numerous set requests exceeding the cache size, you risk evicting all elements from the cache. Malicious actors can exploit this by sending numerous unused requests, evicting all cache elements.

A solution is to use two or more queues or generations. The first queue, accounting for 10-20% of the size, stores new elements, while the second retains elements that have been accessed. Thus, numerous set requests would only impact the first queue, leaving the second unaffected.

Varied Data Workloads

Caches serve various scenarios like CDNs, request caches, database caches, and CPU caches. Each has unique workloads and may require distinct cache algorithms. While there are general algorithms suitable for most cases, specific requirements might necessitate testing various algorithms.

Choosing the Right Cache Size

Cache size has a significant effect on the percentage of hits. Insufficient cache size leads to frequent misses, especially when using a single queue LRU cache. It is very important to analyse your workloads and select an appropriate cache size.

Concurrent Access

I won’t address this topic since Node.js doesn’t present such challenges when designing cache structures. However, there have been instances where concurrency issues led to outages, as seen with facebook, honeycomb, coinbase

Not hitting caches

Some changes can create a situation where you had a 95% cache hit, but after the change the cache hit is down to 50%. Thus, you need to have a lot of new resources to handle this traffic. In general, the cache makes resource scheduling more difficult.

S3-FIFO Cache Algorithm

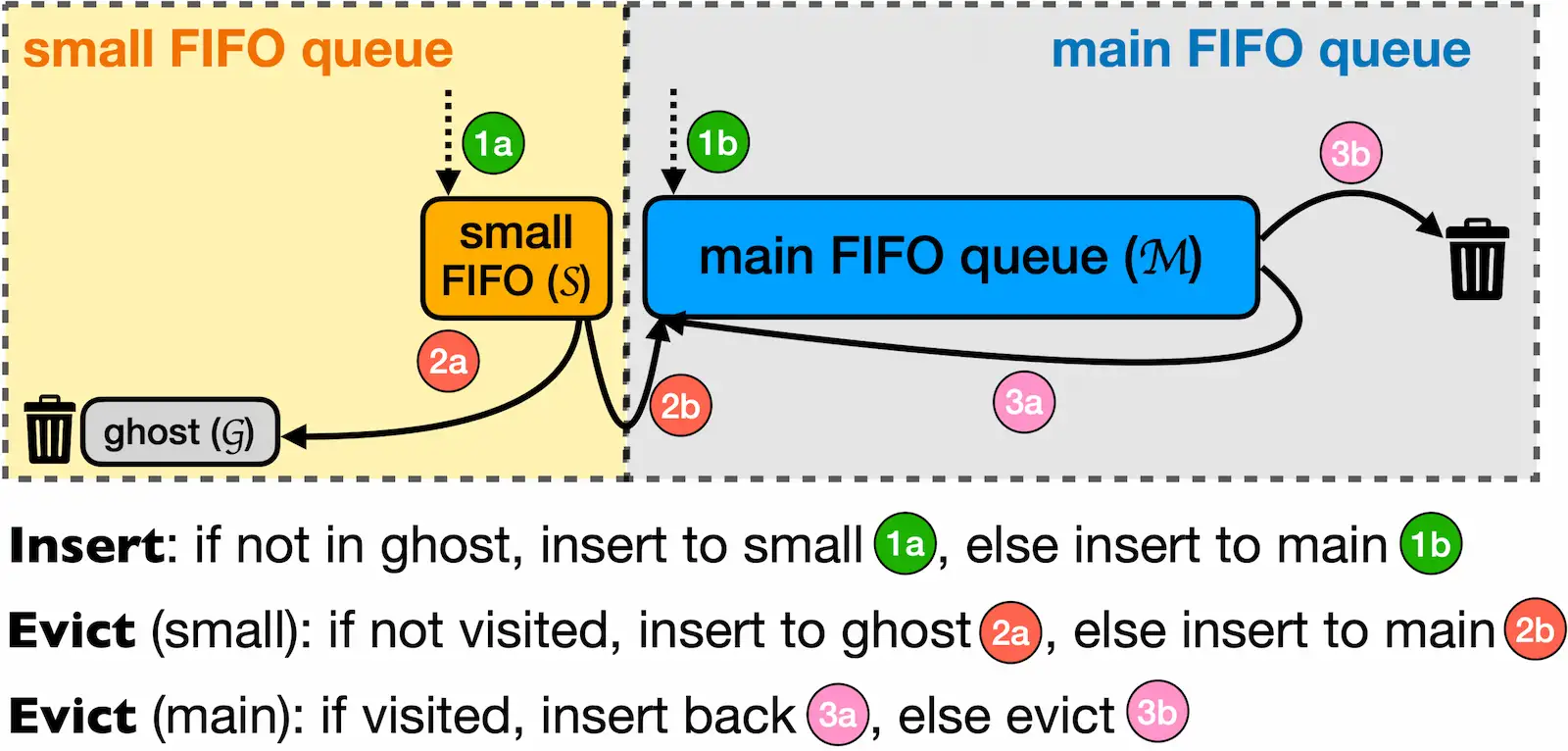

(I sourced this image from the s3-fifo paper)

(I sourced this image from the s3-fifo paper)

Recently, I came across a new paper introducing the S3-FIFO cache algorithm. This algorithm seems neither complex nor difficult to implement, yet it often outperforms the LRU cache. Therefore, I decided to give it a try.

The S3-FIFO is built on three main components:

- Small queue

- Main queue

- Ghost queue

All these queues utilize a similar data structure, which could be a DoubleLinkedList or a variation of Deque.

Small Queue

All new elements are first placed in the small queue. This helps mitigate Popularity Attacks and ensures that the main queue isn’t affected by elements that have only been accessed once. It occupies about 10% of the total cache size.

Main Queue

This is the primary storage of S3-FIFO. It holds elements that have been accessed at least twice.

Ghost Queue

The most intriguing aspect of this algorithm is the Ghost queue. It only stores the keys of elements that have been evicted from the Small queue. Given that the Small queue is just 10% of the cache, there’s a high likelihood that popular keys might be removed. To address this, S3-FIFO uses the Ghost queue. If a new element is found in the Ghost queue, it’s automatically transferred to the Main queue.

This design prevents Popularity Attacks and protects the main queue from elements accessed only once.

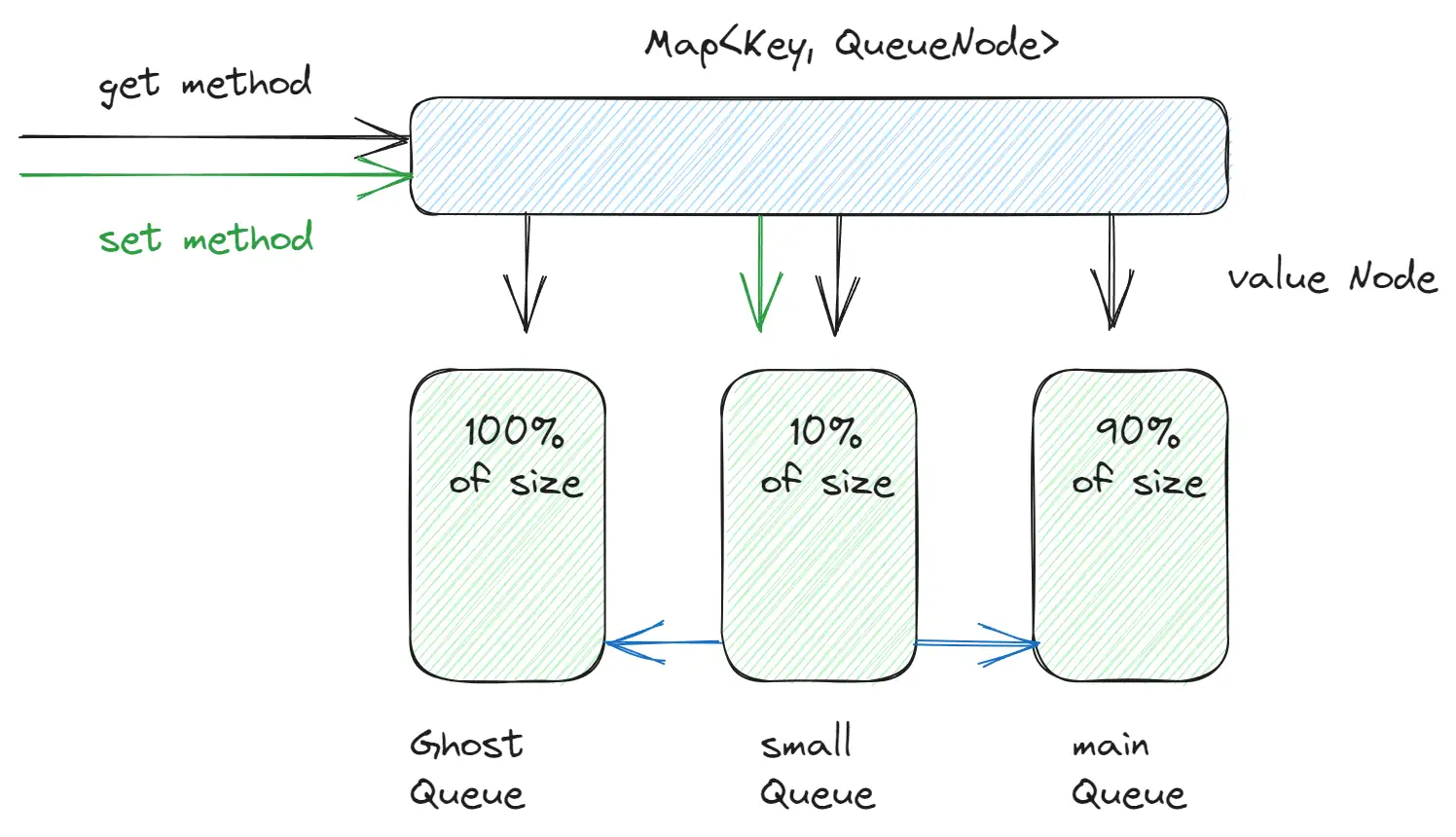

My Implementation

My implementation relies on two data structures: a Map and 3 DoubleLinkedLists. The Map contains:

- key = cache key,

- value = link to the DoubleLinkedList node (object).

This setup ensures that all operations, whether adding, removing, or changing, have a time complexity of O(1). I use the DoubleLinkedList to determine the age of an element. Additionally, the DoubleLinkedList allows for the removal of nodes from the middle of the list in O(1) time.

I use one global map for all items in all queues. This helps me move items between queues without additional Map operations

As a result, I achieved a time complexity of O(1).

I also experimented with different queue implementations, such as Single linked lists and two Stacks, but they performed worse.

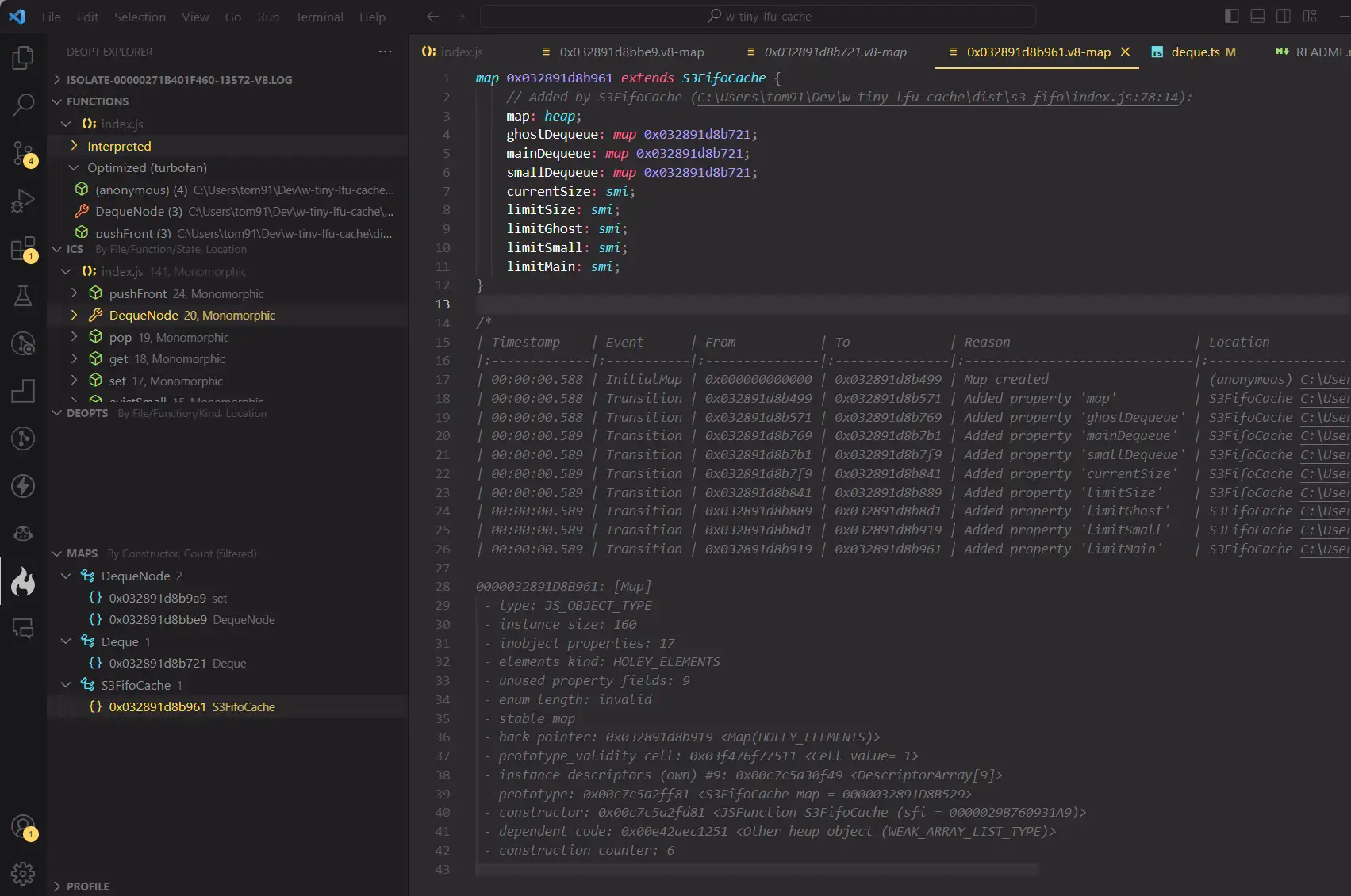

Identifying Deoptimizations in My Code

In the past, I’ve come across information about the potential to collecting V8 profile data to enhance my code. Now, I’ve decided to explore this further.

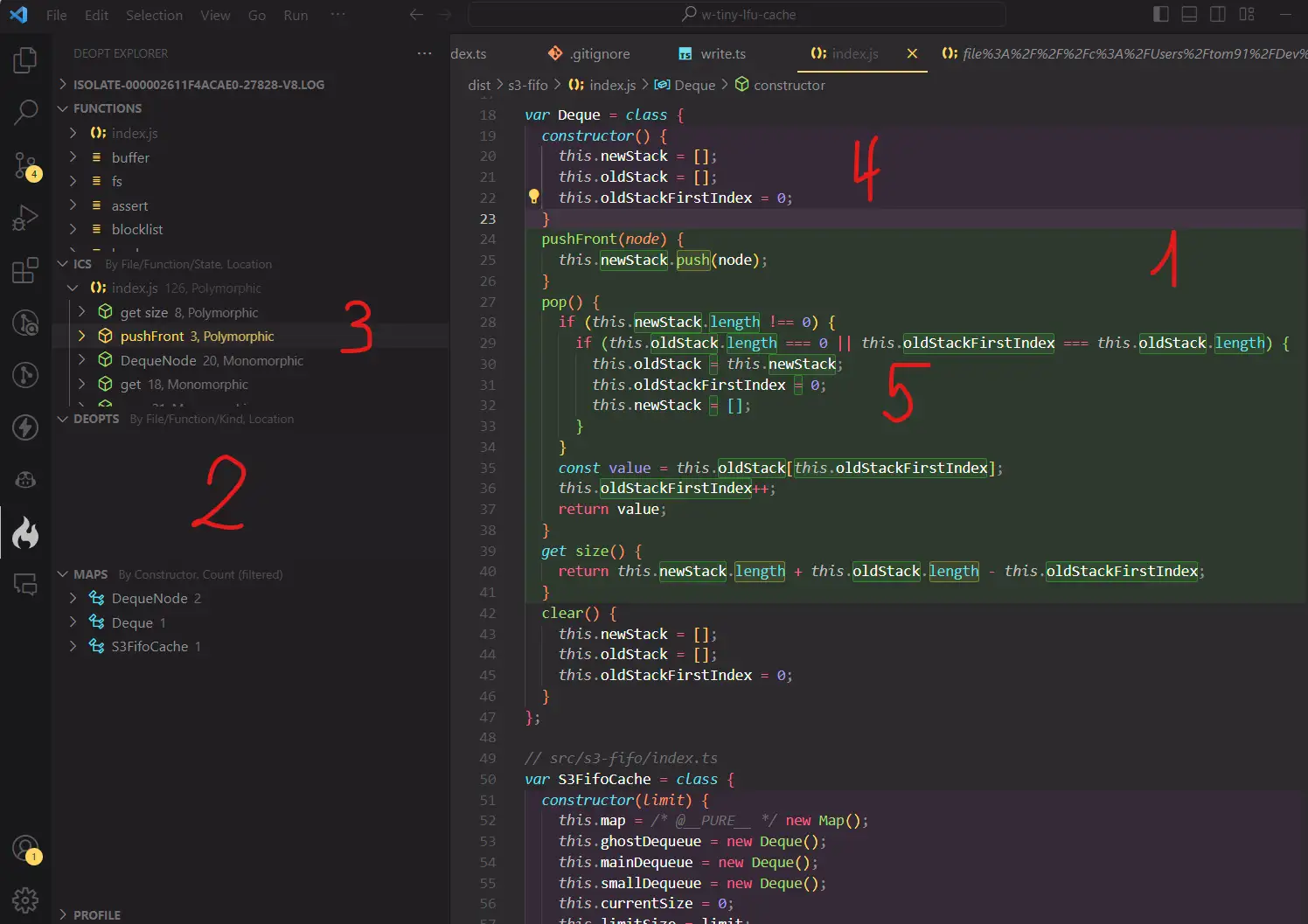

I used the VS Code extension deoptexplorer-vscode to generate a V8 profile and present the report in a user-friendly manner.

Deoptexplorer helps to:

- Identify the objects (maps) created in your program. By default, V8 uses hidden classes to generate optimized code. It’s crucial to minimize variations of the same object.

- Understand how V8 optimizes your code. V8 has 4 execution modes: interpreted, ignition, turbofan, and sparkplug. It’s vital to ensure frequently executed code is optimized with turbofan.

- Recognize variable types: Monomorphic, Polymorphic, or Megamorphic. Monomorphic is ideal as it allows V8 to optimize for a single case, while Megamorphic can disable V8 optimizations.

From the report:

- (1) Green indicates optimized mono-morphic code.

- (2) The deopts panel displays deoptimized code. This library has no deoptimizations.

- (3) Some code sections have a Polymorphic status, indicating varied data types.

- (4, 5) This is due to the variables this.newStack and this.oldStack. They have different hidden classes, and in (5), there’s a switch between these classes, leading to less optimized code.

This issue arose because this.newStack transitioned from the PACKED_ELEMENTS type to the PACKED_SMI_ELEMENTS type during execution. Initially, I used a two-Stack approach for queue implementation. Upon discovering this, I sought a solution but couldn’t find one. However, experimenting with different data structures led me to the DoubleLinkedList, which didn’t have this issue and was faster.

This panel displays the object’s connections, data types, hidden class creation times, and object types.

While this report wasn’t immensely helpful this time, I plan to use it in future articles. A side note: if, for instance, an LRU cache is heavily used in a large application in many places, it might cause V8 deoptimizations, especially if get/set methods are invoked with varied object types, leading to method deoptimization.

Comparing Cache Algorithms

In the following section, I will compare s3-fifo with other renowned cache libraries in Node.js. Let’s delve into their inner workings.

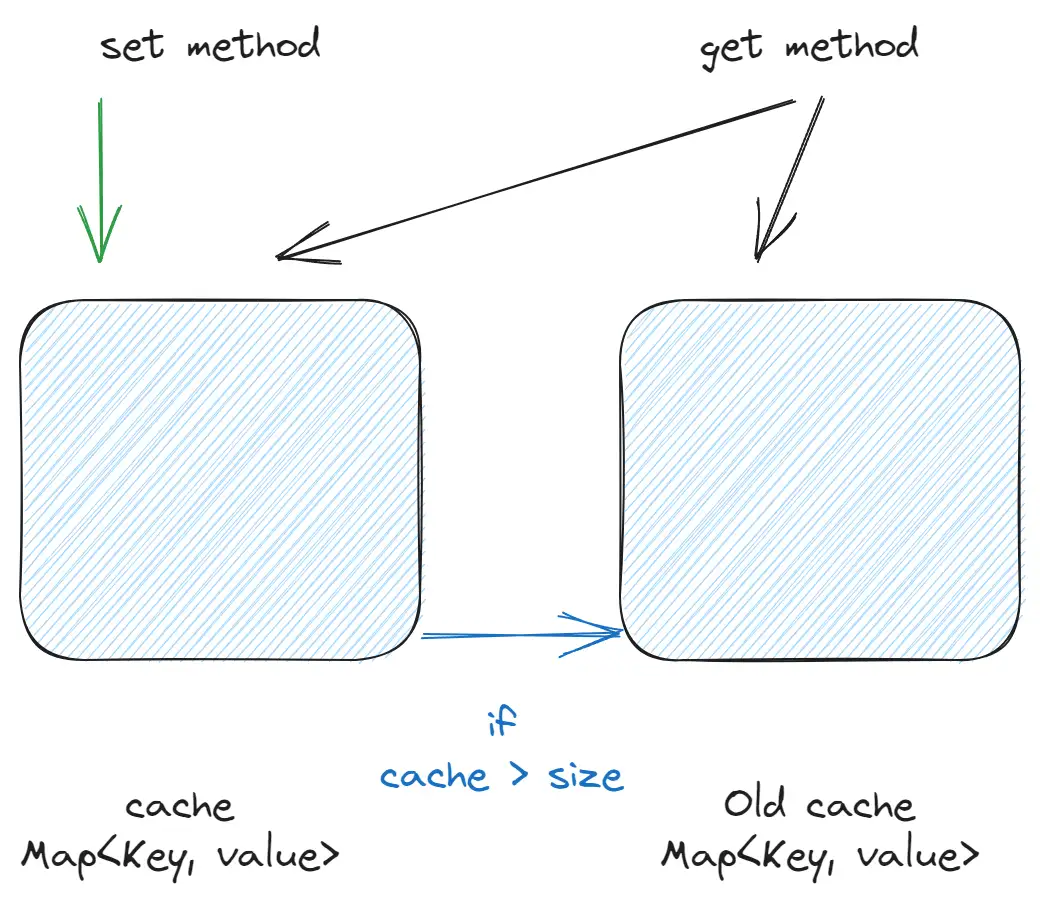

2Q Cache Algorithm

This might be one of the simplest implementations of a limited cache. It requires two Maps (hash maps). When the first Map exceeds its size limit, elements are transferred to the second Map.

- Time complexity: O(1).

- Vulnerability: Susceptible to Popularity Attack.

- For example:

quick-lru

It’s a suitable algorithm to discuss during interviews, especially if tasked with implementing a cache algorithm from scratch.

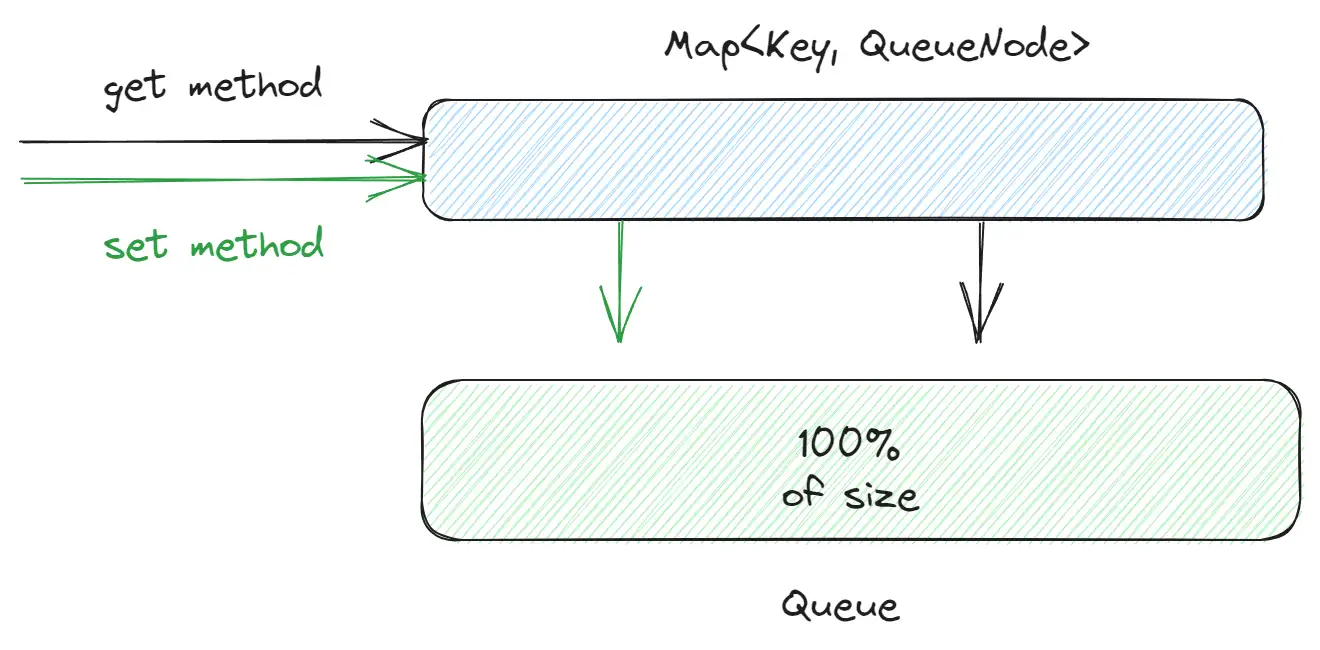

LRU Cache Algorithm

This is a fundamental and widely-used algorithm. For its implementation, you need a Map (hash map) and a queue (implemented as a doubly linked list). The Map holds pointers to nodes in the doubly linked list. When an element is accessed, it’s moved to the front of the queue. If the cache exceeds its size limit, the element at the end of the queue is removed.

- Time complexity: O(1).

- Vulnerability: Susceptible to Popularity Attack.

- For example:

lru-cache,tiny-lru

Benchmarks

In general, cache memory can be measured by two parameters:

- Speed

- Hit rate

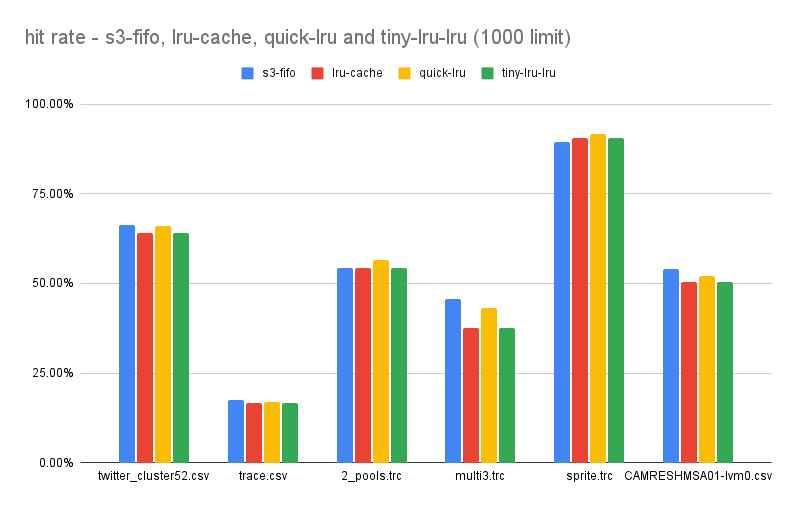

Hit Rate

The good news for me was that hit rate is very easy to measure and this number is stable. I also found a lot of trace logs from different companies on the Internet. Trace logs are information about how users access information. For example, what object was accessed in CDN (for example)

Based on this code:

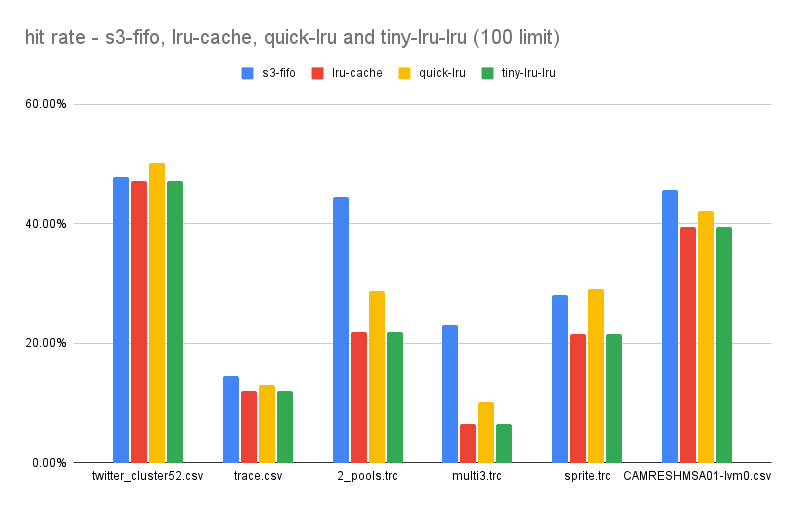

These are the results I got with a cache size of 1000. Total results (sum of all hits)

These are the results I got with a cache size of 1000. Total results (sum of all hits) s3-fifo=327, lru-cache=314, quick-lru=326, tiny-lru=314

Note: quick-lru stores twice the set limit of elements. For instance, if you set a limit of 100, the actual count could reach 200. Hence, these figures might not accurately represent the hit rate for a comparable memory usage.

For a cache size of 100, the results were:

For a cache size of 100, the results were: s3-fifo=203, lru-cache=148, quick-lru=173, tiny-lru=148.

Overall s3-fifo is better in cases where the cache size is smaller than optimal. But these are not the numbers I expected.

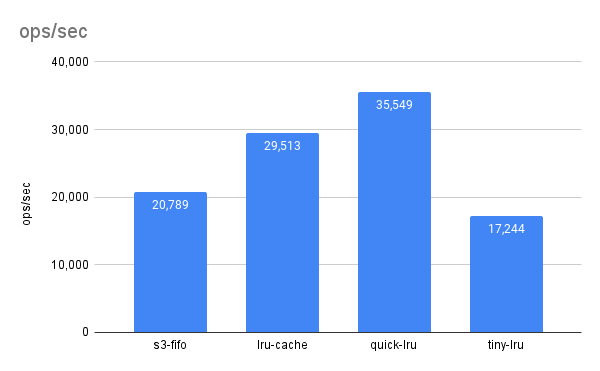

Performance

The performance was nearly half as efficient as the lru-cache library. The lru-cache employs several optimization techniques, such as a well-implemented doubly linked list and predefined array sizes. I haven’t yet integrated these optimizations because the hit rate results were not compelling enough, leading me to explore other algorithms.

The size of s3-fifo is 2.3kb, which compresses down to 0.8kb after gzip. However, other algorithms, like the 2Q used in quick-lru, might have a smaller size.

Conclusion

Initially, s3-fifo seemed promising, especially since the document highlighted significant improvements over the LRU cache. However, my implementation didn’t yield similar results. I also reviewed the canonical implementation by the document’s author and found comparable outcomes. On the other hand, I’m aware of another algorithm, w-tiny-lfu, which has been integrated into several high-speed cache libraries for Java, Golang, and Rust. It boasts impressive results, albeit being more intricate than s3-fifo. I plan to delve into this in a subsequent article.