NewSQL databases are not widely discussed in the database world. Typically, discussions revolve around SQL databases like PostgreSQL or MySQL, or NoSQL options like Cassandra or MongoDB. However, NewSQL offers strict consistency along with high scalability, which is quite exciting and raises many questions about how this is achieved. In this article, I will highlight the main components that differentiate NewSQL databases from SQL and NoSQL databases. This article should prove useful for engineers who wish to understand how databases function and how to select the appropriate database for their specific needs.

Generation of databases I propose categorizing databases into three distinct generations. While this does not represent all generations or types, it aids in explaining the ideas and advancements between generations.

SQL databases

Databases such as PostgreSQL, MySQL, Oracle, and others were developed starting in the 1990s. At that time, the guarantee of consistency and transaction support was crucial. Services typically operated a single database instance that stored all data for the service or organization and was accessed by a limited number of users. This type of database is best suited for these scenarios.

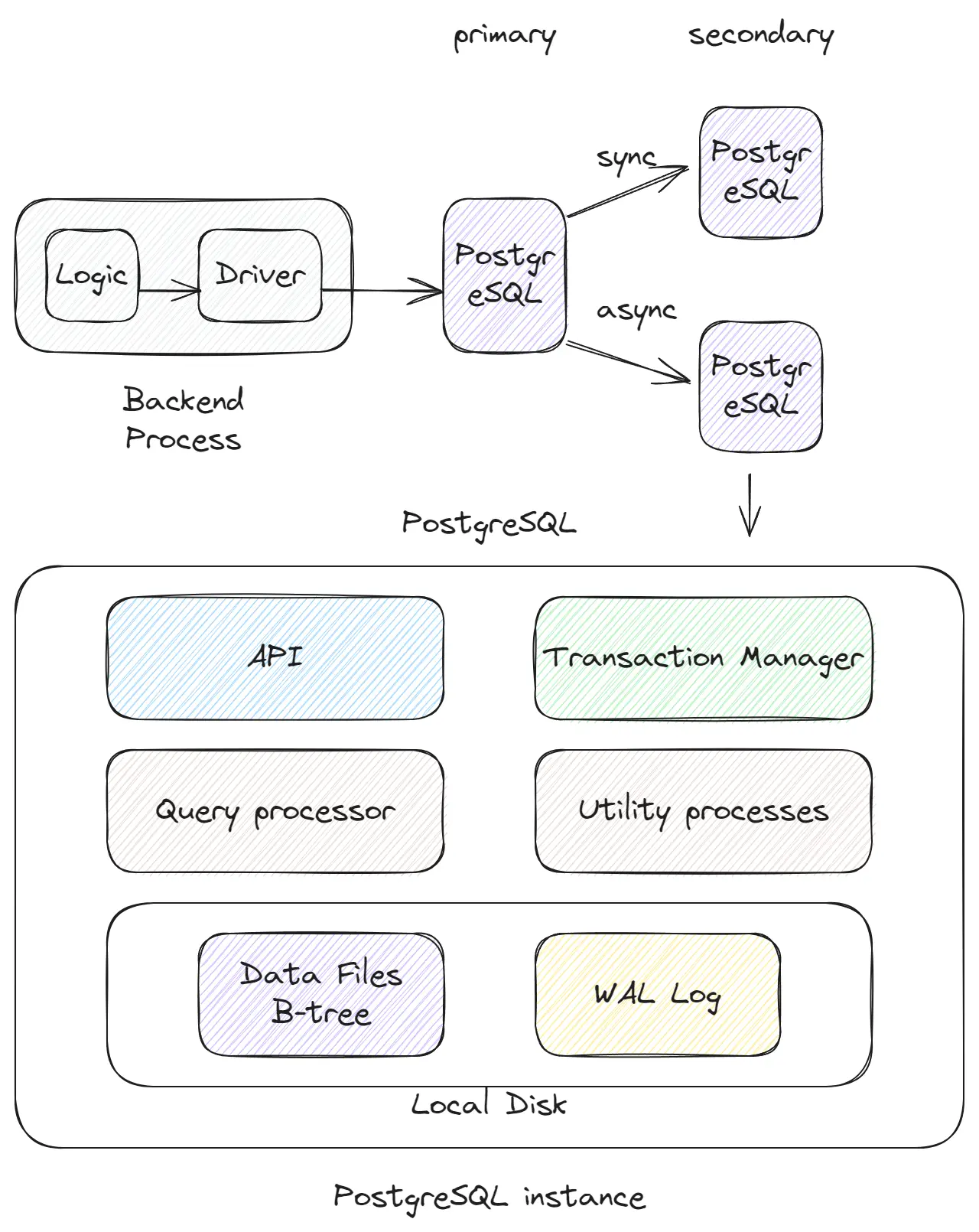

High-level components of SQL databases

- API: The layer of communication between the client and the database.

- Query Processor: The layer that parses and executes SQL queries. SQL is rich in syntax, and this layer is capable of understanding queries, creating execution plans, optimizing, and executing them.

- Transaction Manager: Maintains all logic related to transactions and consistency.

- Data Files B-tree: The storage structure of the database that holds all table data. It is typically a B-tree, which provides logN performance for read operations.

- WAL (Write-Ahead Logging): This is like a file that only appends new information, such as insert, update, and delete operations in databases. Its append-only nature makes it very fast, and it is crucial for data integrity if the database crashes before the data files are updated.

Advantages of typical SQL databases

- Transactions: This refers to how data is changed in the database. SQL databases support ACID properties (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) which ensure that changes are not lost and do not compromise the integrity of the database.

- Consistency: Guarantees that our data will have a predictable value when we read data and perform transactions. By default, SQL databases provide OK consistency guarantees. The lower the level of consistency, the more careful we need to be when working with data.

- Speed: SQL databases are fast enough for typical and primary usage. The B-tree structure provides good average performance for both read and write operations. Of course, there are specific databases that are much faster for particular uses like analytics or caching. However, for standard services, SQL databases are good enough.

- Simplicity: Databases of this type are simpler from an infrastructure perspective. Additionally, transactions and consistency simplify the development of the system.

The majority of the advantages of SQL databases stem from the fact that we have a single instance of the database, which eliminates the need to think about how to synchronize data across different servers.

Disadvantages of Typical SQL Databases

- Limitations in Scaling: Having a single database instance can challenge integration and scaling with additional instances. PostgreSQL, for example, lacks the functionality to communicate with other PostgreSQL instances. To scale, we need to write, purchase, or install additional tooling. There are many companies providing tools to scale PostgreSQL.

- Expensive Scaling: If we implement all the necessary tooling and services on top of PostgreSQL, we may experience lower performance per CPU than in an ideal case. This is because CPU utilization will be lower in scenarios where some instances do not handle requests if we aim for high consistency.

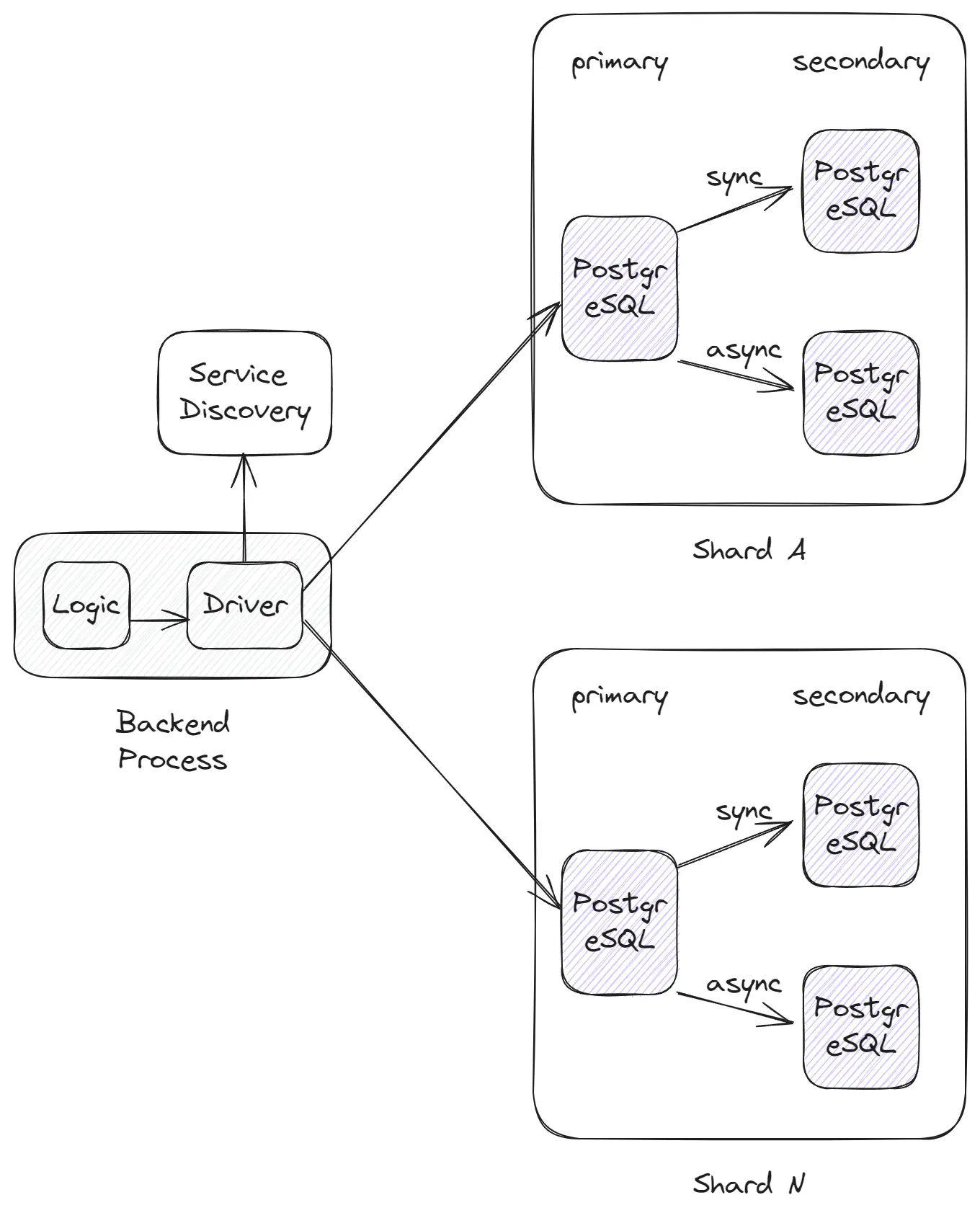

In the real world, relying on just one database instance is not appropriate because of the importance of availability and scalability. Therefore, we often choose a pattern where we have one Primary node that supports both read and write operations, and backup Secondary nodes that use synchronous and asynchronous strategies. This approach enhances the availability of the database; if a server goes down, we will not lose data and can recover quickly. Additionally, we can use the Primary node for write operations and multiple Secondary nodes for read operations to increase the number of read operations, although this reduces the level of consistency of read operations to an eventual consistency level.

Sharding

Another challenge is Sharding. Sharding is the process of distributing data across different database instances. For example, we might have five shard instances, each with one Primary Instance and one or more Secondary instances that hold a portion of the table’s data based on sharding logic. It’s a complex process that requires many tools, and the main issue is that sharding introduces many problems associated with distributed systems that are not addressed in typical databases like PostgreSQL or MySQL. As a result, we lose the guarantees of consistency, transactions, and indexes that come out of the box and need to implement them using additional tools and services.

SQL databases are best if they are suitable for your needs, or if you have the tooling to overcome these limitations. However, to address scalability issues, a new type of database was introduced: NoSQL databases.

NoSQL databases

NoSQL can be compared to a marketing brand created to signify the introduction of a new type of database distinct from the previous SQL generation. Introduced around 2009, this term encompasses various database types like Key-Value, Document, Column, and Graph, each ideal for different applications. Examples include Cassandra, MongoDB, HBase, and DynamoDB.

A primary difference between SQL and NoSQL databases is their enhanced scalability with lower consistency guarantees. Typically, NoSQL databases introduced in an era when companies managed a lot of amounts of data across numerous database instances. So, NoSQL inherently provides tools to facilitate the creation of database clusters with multiple instances for data storage.

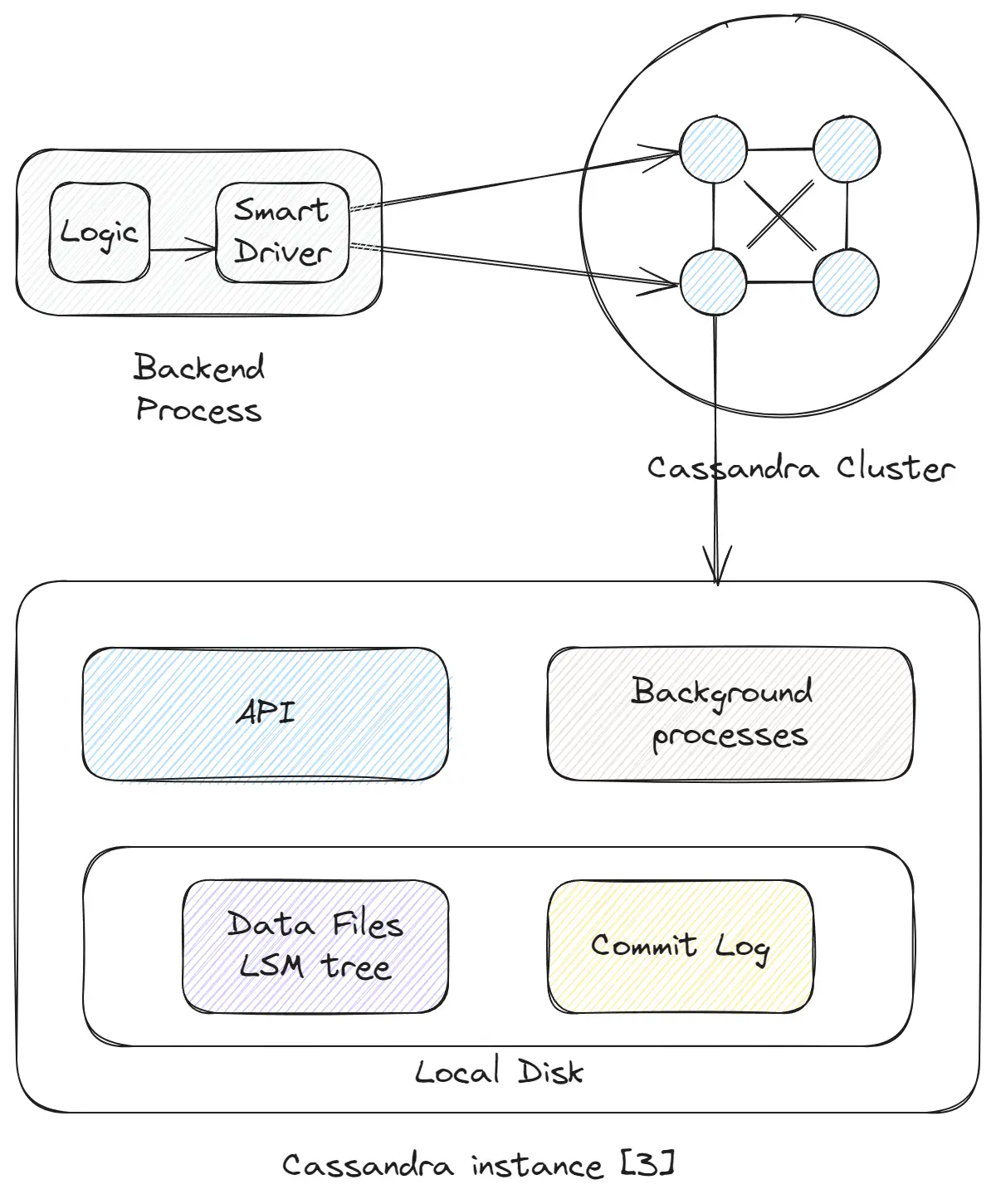

High-Level Components of NoSQL Databases (Using Cassandra as an Example)

The setup comprises numerous interconnected instances. Fundamentally, little has changed from SQL to NoSQL. There are still database instances, and data is stored locally. However, there is reduced functionality with more focus on the database type. Each instance includes:

- API: Similar to the API of SQL databases, but with additional logic for managing connections between instances and intelligent database clients, or an extra layer of proxy included out-of-the-box.

- Commit Log: Comparable to the write-ahead log in SQL databases, it serves to prevent data loss in the event of a crash.

- Data Files LSM Tree: This may be an LSM-tree or B-tree (as in MongoDB, DynamoDB), essentially mirroring SQL databases. The databases store and read data from a server’s local storage.

- Background Processes: These are responsible for tasks such as compaction, repair, and synchronization between instances.

Advantages of Typical NoSQL Databases

- Scalability: NoSQL databases are designed for scalability. They typically support sharding and replication right out of the box. For instance, with Cassandra, it’s possible to create a cluster of 100+ database instances that manage table data and deliver robust performance for both read and write operations. This is achievable due to the databases’ inherent logic for inter-instance connections, smart database clients, or an inbuilt proxy layer.

- Resource Utilization: The architecture of NoSQL databases is optimized for distributed systems, which promotes efficient resource utilization through simultaneous read/write operations across multiple instances.

Disadvantages of Typical NoSQL Databases

-

Consistency: These databases often provide only causal or eventual consistency or tunable consistency (like Cassandra) with limitations. Engineers must put extra effort into adapting the architecture to these constraints.

-

Complexity: The complexity is in two aspects. Firstly, the system itself is more complex as it attempts to address common distributed system challenges. Secondly, it introduces complexity for the users who must consider these limitations. For example, in Cassandra, data design is crucial; incorrect design can lead to significant performance and consistency issues, more so than with SQL databases.

-

Functional Limitations: SQL databases come with a rich set of features like transactions, indexes, joins, triggers, etc. NoSQL databases, on the other hand, often lack these features or struggle to implement them effectively.

As a result, while NoSQL databases offer impressive scalability, they encounter challenges with consistency. To address these consistency issues, NewSQL databases were introduced.

NewSQL databases

NewSQL databases blend the advantages of SQL and NoSQL databases but add complexity and increase latency, with writing operations exceeding 40ms. These databases range from Serializable to Strict Consistency, offering a higher level of consistency than typical SQL systems, along with excellent scalability. Examples of NewSQL databases include Google Spanner, FaunaDB, YDB and others.

Databases as Complex Systems

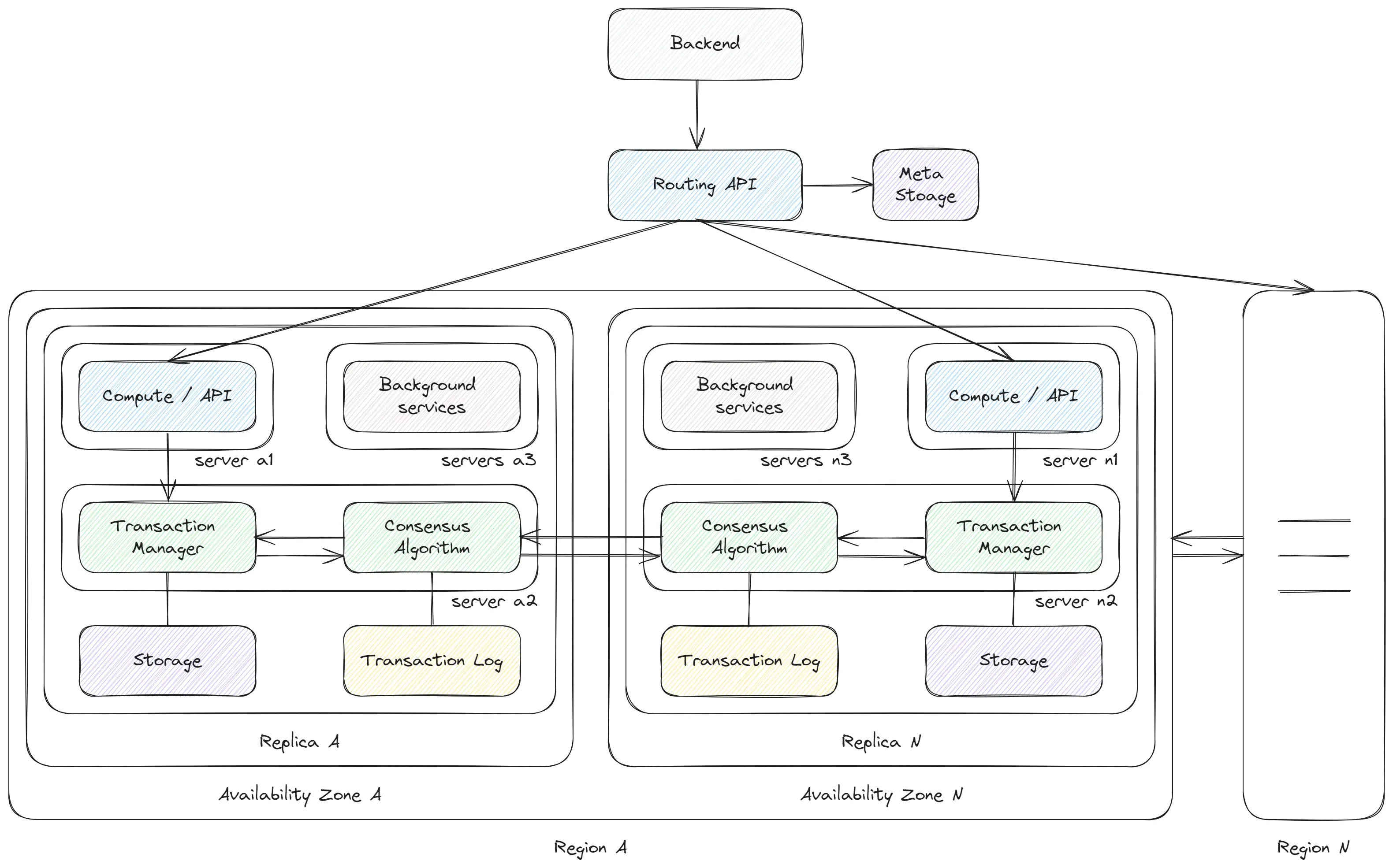

NewSQL databases are complex systems consisting of:

- Routing Layer: Directs requests to the appropriate replica. Data is divided across multiple replicas, needed a mechanism to identify the correct replica for each request. This is typically achieved through range-based sharding.

- Compute Layer: Functions similarly to an API previously, but is a separate process that can be scaled independently. The number of instances varies based on the request load.

- Transaction Manager: A distinct service that implements the core logic of the database. Write and read operations must be consistent and return the latest data. To ensure this, databases employ consensus protocols such as Raft or Multi-Paxos. These protocols facilitate agreement across different replicas to guarantee data consistency. Consensus is also required for read operations to ensure the retrieval of the most recent data.

- Storage Layer: With the ability to scale the compute layer independently, it’s necessary to decouple the database instances from storage. Traditional databases stored data on local disks, but modern approaches utilize distributed storage systems like Google Colossus, DFS, or SeaweedFS, which handle data replication and scaling independently. At the file level it can be the same LSM-tree or B-tree.

- Transaction log - Similar to SQL databases, NewSQL databases require tracking all state changes. This is accomplished using a distributed log containing data from the consensus algorithm. As a result, all instances maintain the same sequence of changes, which can then be applied to the storage layer.

- Background Jobs - NewSQL services perform numerous background tasks. These include compaction, splitting shards into smaller ones, and auto-scaling ‘hot’ shards, across other maintenance activities.

Scalability with Guarantees

The most intriguing aspect of NewSQL databases is their approach to distributed transactions and high consistency. This requires new methods designed for distributed systems.

Consensus Protocols

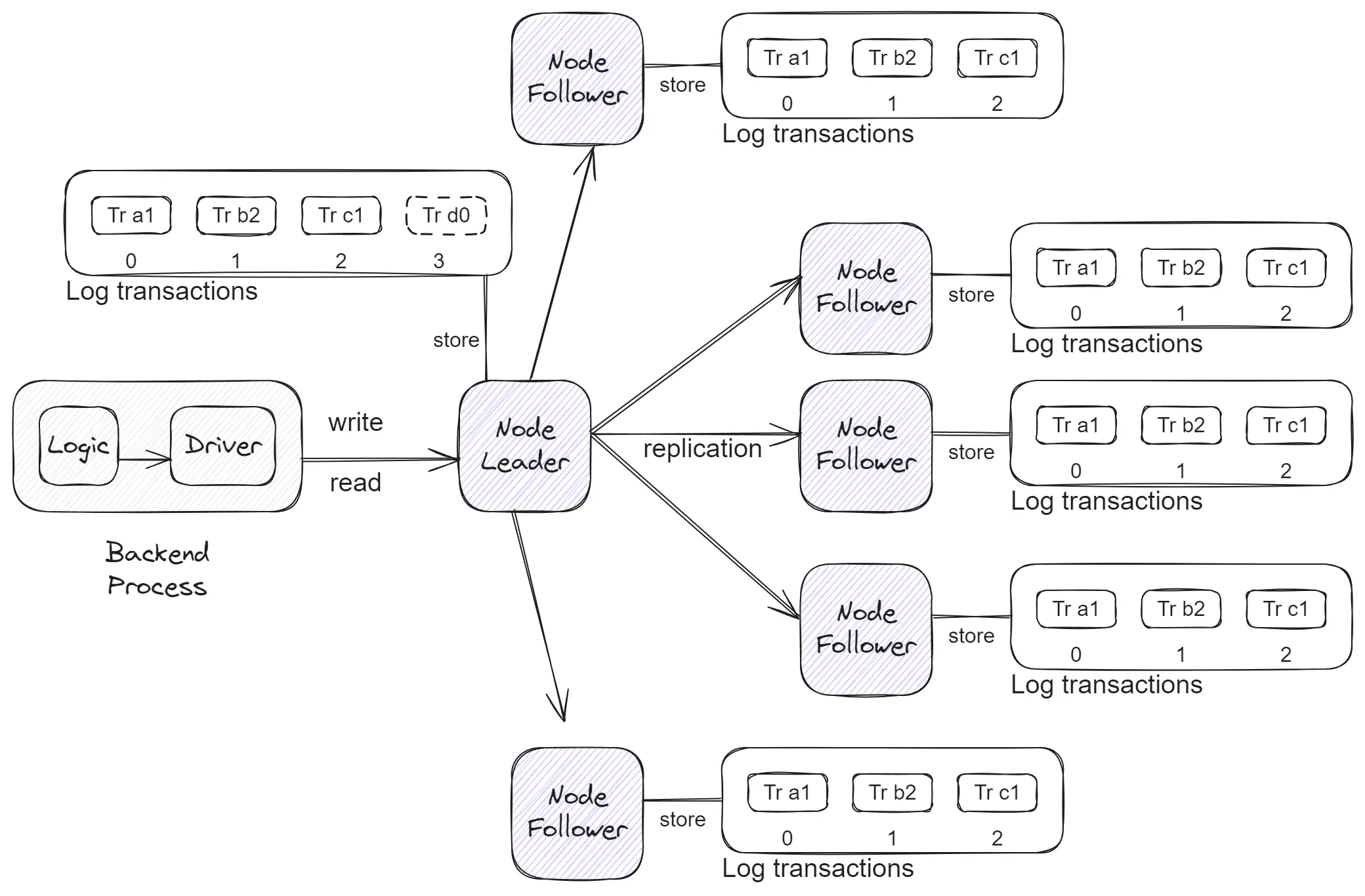

Protocols like Raft and Multi-Paxos enable consistent changes across different servers. They are core components to many distributed systems that require consistency.

Core Components of Consensus Protocols:

- Nodes: Typically, there are more than five nodes hosted across different Availability Zones.

- Leadership: At any given time, there is either one leader node or none, with the system in the process of electing a new leader.

- Raft Log: Raft utilizes a log that operates on the State Machine Replication (SMR) principle, ensuring each node has identical data in the same sequence.

- Communication: The leader communicates with followers approximately every 50ms, resulting in numerous inter-node requests.

- Majority Approval: To write data, the leader requires approval from a majority (over 50%) of the follower nodes.

- Leader Election: If the leader fails to send ping messages to followers, they initiate a new leader election after a timeout of (150 * random)ms.

Simplifying the details, it’s similar to a single instance of an SQL database where only changes are applied, and these changes come with strong guarantees of availability, even if the leader node fails.

Paxos or Multi-Paxos or Raft

Paxos was originally created in 1989, a time before the widespread adoption of distributed systems. The original paper presented the main concepts through a complex analogy with the political system of Ancient Greece (and this is no joke). The protocol was forgotten for 12 years. In the 2000s, it began to be implemented in systems, despite many unresolved issues. Plain Paxos lacked a single leader, leading all nodes to attempt writing new data to the log, which necessitated extensive communication and write attempts. Multi-Paxos was introduced to reduce the number of requests by designating a single leader. The Raft protocol was developed to further simplify the implementation and solve the main problems of the Paxos protocol. Raft operates similarly to Multi-Paxos but is easier to use. However, Raft like frameworks have their limitations. Currently, if Raft is suitable for a system, it is preferable to use it; otherwise, Multi-Paxos can be adapted to meet specific requirements.

A good visualization of this process can be found here:

Read Path of Data in FaunaDB

- The client sends a request to the routing layer.

- The routing layer, based on replica information, forwards the request to the Compute Layer.

- The Compute Layer then sends the request to the Transaction Manager.

- The Transaction Manager verifies whether the replica is up-to-date (based on the epoch and consensus protocol data). It requires to make a request to the Consensus Leader to verify the replica’s status.

- If the replica is current, the Transaction Manager relays the request to the Storage Layer.

- The client receives a response.

Distributed transactions

Our system already utilizes a Consensus protocol, which provides a distributed log. This log contains all data in the same order for all replicas, recording all changes to the state of our database such as insert, update, delete, and table changes. If we maintain the same order, we can achieve Linearizability. However, our transactions can encounter conflicts; for instance, two different transactions may attempt to modify the same row simultaneously. These transactions are written into the log, and if applied, they could result in data conflicts. To address these issues, we need to employ additional methods like 2PC or Calvin to resolve transaction conflicts.

2PC (Two Phase Commits)

This is a widely-used approach to implement distributed transactions, commonly used in SQL, NoSQL, and NewSQL databases. The process unfolds in a few phases:

- The leader creates a

Preparemessage for all replicas, requesting them to prepare for the transaction. If any replica detects a conflict with the transaction, it will return an error, and the transaction will be canceled (Abort message). - The leader then sends a

Commitmessage to all replicas. The replicas proceed to write the changes into the system. - If there are any issues, or if the majority of replicas do not return an ‘OK’ response, the leader will issue an

Abortmessage, and all replicas will cancel the transaction.

This method requires two additional requests between the leader and all replicas. In installations that use nodes in different locations, this can introduce significant additional latency for write operations, which is exacerbated in global installations across different regions.

Google Spanner uses 2PC but introduces several optimizations. For instance, it creates regional leaders to synchronize data only between these leaders. Additionally, it uses Atomic and GPS clocks to determine the order of transactions across different regions. Despite these optimizations, 2PC still adds a latency of approximately 320ms for multi-continent installations. Reducing the number of requests could potentially decrease this latency.

Calvin

Developed in 2012 and implemented in the Fauna database, Calvin represents an alternative method for implementing distributed transactions without relying on 2PC. Calvin’s design allows transactions to be canceled. It also introduces a new transaction syntax that is closer to code, enabling the description of the data reading process and handling edge cases, such as when data was created or cannot be updated. This syntax, similar to typical JavaScript code:

Let({

// Define the input parameters for the new task

userId: "someUserId",

taskDescription: "Finish writing FQL article",

taskPriority: "High",

// Attempt to find an existing task with the same description for the user

existingTask: Match(Index("tasks_by_user_and_description"), ["someUserId", "Finish writing FQL article"])

},

If(

// Check if the task already exists

Exists(Var("existingTask")),

// If the task exists, update its priority instead of creating a duplicate

Update(

Select("ref", Get(Var("existingTask"))),

{ data: { priority: Var("taskPriority") } }

),

// If the task does not exist, create a new task

Create(Collection("Tasks"), {

data: {

userId: Var("userId"),

description: Var("taskDescription"),

priority: Var("taskPriority"),

createdAt: Now(),

completed: false

}

})

))After SQL with insertion, it looks strange, but this concept helps to make transactions that can be applied to multiple scenarios without conflicts in the data because we have if statements and other operations.

Data Write Path in Fauna DB:

- The Backend Client sends a request to the routing layer.

- The routing layer, informed about the replicas, forwards the request to the Compute Layer.

- The Compute Layer sends a request to the Transaction Manager and subscribes to the transaction status.

- The Transaction Manager performs a dry-run of the transaction, saving the result without applying changes, and appends the transaction with values to the Consensus Algorithm.

- The Consensus Algorithm appends and synchronizes the transaction across all replicas, then notifies the Transaction Manager of new transactions.

- The Transaction Manager executes the transaction and applies changes to the Storage Layer. Since all replicas have identical data in the same order, there’s no need to verify the transaction’s success across all replicas. If a transaction is applicable in one replica, it can be applied to all.

- The Transaction Manager informs the Compute Layer of the transaction status.

- Finally, the Backend Client receives information about the transaction status.

We still have issues with conflicting transactions. However, FaunaDB adds the final result of a transaction. If the values are not consistent across replicas, the transaction will be canceled. The replica that initiated the transaction will be notified and will recreate the transaction.

This approach allows transactions to be completed in one operation instead of two, as in the Two-Phase Commit (2PC) protocol. Consequently, the latency of write operations can be twice as low compared to the 2PC solution. According to FaunaDB’s status, the median latency for write operations is 40ms. In more complex scenarios, it may approach 150ms, but it is still significantly better than the 2PC solution.

Advantages of NewSQL Databases

- High Consistency: NewSQL databases provide strong consistency guarantees due to their use of consensus protocols and distributed transactions.

- Scalability: These databases inherently support sharding and replication. Their design also allows for independent scaling, which enhances overall scalability.

Disadvantages of NewSQL Databases

- High Latency: While NoSQL databases like Cassandra can achieve 1ms latency for write/read operations within a single availability zone, NewSQL solutions often have higher latency. This is because they require the use of a consensus protocol, which takes additional time.

- Complex Technologies: The inner workings of NewSQL databases involve complex concepts such as consensus protocols, distributed transactions, distributed storage, and distributed logs. These require additional knowledge and expertise.

- Lack of Popularity: Open-source databases like TiDB, YDB, and CockroachDB are less popular than traditional SQL or NoSQL databases. Top-tier databases like Google Spanner or FaunaDB are not open source and require payment for their use. Consequently, it is challenging to find skilled engineers familiar with these types of databases.

We gain guarantees and scalability, but at the cost of increased latency and complexity. Any changes necessitate a consensus, which requires more time compared to NoSQL databases.

Conclusion

SQL databases offer strong guarantees but need additional tools for scaling. NoSQL databases good in scalability but provide fewer guarantees. NewSQL databases offer both guarantees and scalability but at the expense of increased time and system complexity.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution; each has its advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, we must choose according to the problem at hand. Not all systems require global high consistency, making NewSQL databases an overkill in many scenarios, potentially leading to issues with latency and costs.